Evidence-based practice begins and ends with the patient. It is the intersection of clinical expertise, best research evidence, and patient values and preferences.

Five Steps of Evidence-Based Medicine/Practice:

ASK: Create a clinical question based on your assessment of the patient

ACQUIRE: Find the right resource(s) and conduct the search

APPRAISE: Critically appraise the evidence

APPLY: Apply the results to patient care

ASSESS: Evaluate the outcome

Background Questions

These types of questions may best be answered by information found in textbooks or narrative review articles in journals.

Example: What are the complications of gastroesophageal reflux?

Foreground Questions

Foreground questions ask for specific knowledge to help make informed clinical decisions and usually concern a specific patient or population. Foreground questions tend to be more specific and complex compared to background questions. These types of questions often investigate comparisons, such as two drugs, two treatments, two diagnostic tests, etc.

Example: In patients with primary hypertension, are beta-blockers more effective than other antihypertensive drugs for reducing myocardial infarction mortality?

PICO is the most common concept used as a bridge between a clinical question and a search strategy.

Use PICO to build a clinical foreground question. PICO stands for:

Patient/Population/Problem

Intervention, Prognostic Factor, Exposure

Comparison (optional)

Outcome

Example:

A 62-year-old patient’s PSA blood test returned with Level 4 reading. This falls withing the normal range for the patient’s age. However, the patient heard on the news that a PSA test misses 82% of tumors in men under the age of 60 and is concerned about the accuracy of the test.

P - Male patients over 60

I - PSA test (or prostate specific antigen)

C - None (the question is not looking at a comparison)

O - Accurate tool for diagnosing prostate cancer

Clinical Question: In male patients over 60 years old (P), is the PSA test (I) an accurate tool for diagnosing prostate cancer (O)?

In addition to PICO, there are other acronyms used to develop clinical questions, depending on the study’s purpose. For instance, PICOT adds "Time to the equation" and PICOTT adds "Type of Question" and "Type of Study."

Point of Care vs. Comprehensive Research Resources

Point of care resources are typically secondary/background filtered resources that are used at the bedside to provide quick overviews of a topic and seminal research. More comprehensive searches typically use databases to retrieve unfiltered content.

Resources for Point of Care:

ClinicalKey

DynaMed

PubMed Clinical Queries

Trip

UpToDate

VisualDx

Schaffer Library Research Resources:

Cochrane Library

Embase

MEDLINE

PubMed

Web of Science

Practice Guidelines

Practice guidelines recommend best clinical practice based on the highest level of available evidence. You can search for them in many of the resources listed above. For information about literature searches and search assistance, visit our Research & Publishing page.

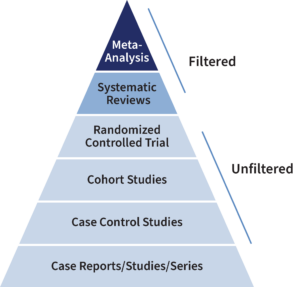

Types of Studies and Levels of Evidence in Hierarchical Order

Meta-Analysis: a statistical analysis that combines results from multiple studies.

Meta-Analysis: a statistical analysis that combines results from multiple studies.

Systematic Reviews: exhaustive, well-documented, structured searches in multiple databases with reproducible results.

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT): study participants are randomly selected to receive, or not receive, an intervention, such as a drug or surgical procedure.

Cohort Studies: longitudinal studies that follow groups of people over time.

Case Control Studies: observational studies that compare different groups of people; one group has a particular disease or condition and the other does not.

Case Reports/Studies/Series: studies an individual or group of individuals of interest.

Question Types Matched to Study Types

Some clinical questions are best answered by certain study types. If the best study type is not available, move to the next level of evidence in the hierarchy.

Examples

Therapy: RCT

Diagnosis: Prospective, blind controlled RCT compared to a gold standard

Prognosis: Cohort study

Etiology/Harm: RCT

Review the evidence for validity and applicability to your patient. Tools that guide critical appraisal:

AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II) Reporting Checklist

BMJ Best Practice EBM Toolkit

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine EBM Tools

JAMAevidence Worksheets (requires personal profile sign-in)

Clinical Calculators

ClinicalKey (select the 'Calculators' link on the ClinicalKey landing page)

DynaMed

JAMAevidence

UpToDate

Based on the critical appraisal, apply the best evidence to your patient. Remember to ensure that the evidence and recommendations incorporate patient values and preferences.

Reflect on the result of incorporating your clinical expertise, the best evidence, and the patient's values and preferences into improving your patient's outcome. Self-evaluate and determine if further evidence is needed or how you could improve your process in the future.

Learn More about Evidence-Based Medicine and Practice

There are many resources focused on evidence medicine and practice. Here are a few ways to learn more.

- Explore a select list of Schaffer Library resources

- Search the Library’s Discovery Tool

- Search the resources listed in Step 2 above

- Read these frequently cited journal articles:

- Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn't Sackett D. BMJ 1996; 312(7023) 71-72.

- The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 128(1): 305-310.

- Obtaining useful information from expert based sources. Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. BMJ 1997; 314: 947.

- The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. ACP J Club 1995 Nov-Dec; 123(3): A12-13.

Contact us for assistance in Evidence-based Medicine: 518-262-5532 | [email protected]